Mixed-Criticality Real-Time Scheduling

Research Motivation

A Mixed-Criticality System (MCS) is a real-time system that comprises tasks having two or more distinct criticality levels (e.g., safety-critical and mission-critical). There are two conflicting trends in the design of such systems. One is that the safety assurance requirements are being increasingly emphasized. The other is that more functionalities are being implemented on integrated platforms due to size, weight and power (SWaP) constraints. Existing scheduling techniques reserve large amounts of computational resources to ensure that every real-time task, including those that are less critical, provide full service even under theoretical worst-case conditions (safety assurance). As a result, the computational resources are highly under-utilized in such systems. To overcome this limitation, the mixed-criticality real-time task and scheduling model was proposed, wherein all tasks are required to provide full service under normal (practical worst-case) conditions, but less critical tasks may only be able to provide degraded service under theoretical worst-case conditions.

Contributions

1. Execution support for less critical tasks

In the conventional mixed-criticality task and scheduling model, the less critical tasks are heavily penalized under theoretical worst-case conditions in order to guarantee resources for the high critical tasks. However, in practice, penalizing the less critical tasks has adverse effects on performance. In this work, we consider the problem of guaranteeing some (potentially degraded) service from the less critical tasks even under theoretical worst-case conditions.

In the conventional mixed-criticality task and scheduling model, the less critical tasks are heavily penalized under theoretical worst-case conditions in order to guarantee resources for the high critical tasks. However, in practice, penalizing the less critical tasks has adverse effects on performance. In this work, we consider the problem of guaranteeing some (potentially degraded) service from the less critical tasks even under theoretical worst-case conditions.

We have developed a component-based mixed-criticality task and scheduling model to address the above problem. The model comprises a component-level design parameter called tolerance limit, which represents the expected number of critical tasks within the component that will simultaneously require additional computational resources during extreme worst-case conditions. We have developed a scheduling strategy based on this parameter such that as long as the critical task requirements are within this limit, the less critical tasks in other components will continue to provide full service. Thus, the component boundaries of the proposed model are designed to provide the isolation necessary to support the execution of less critical tasks.

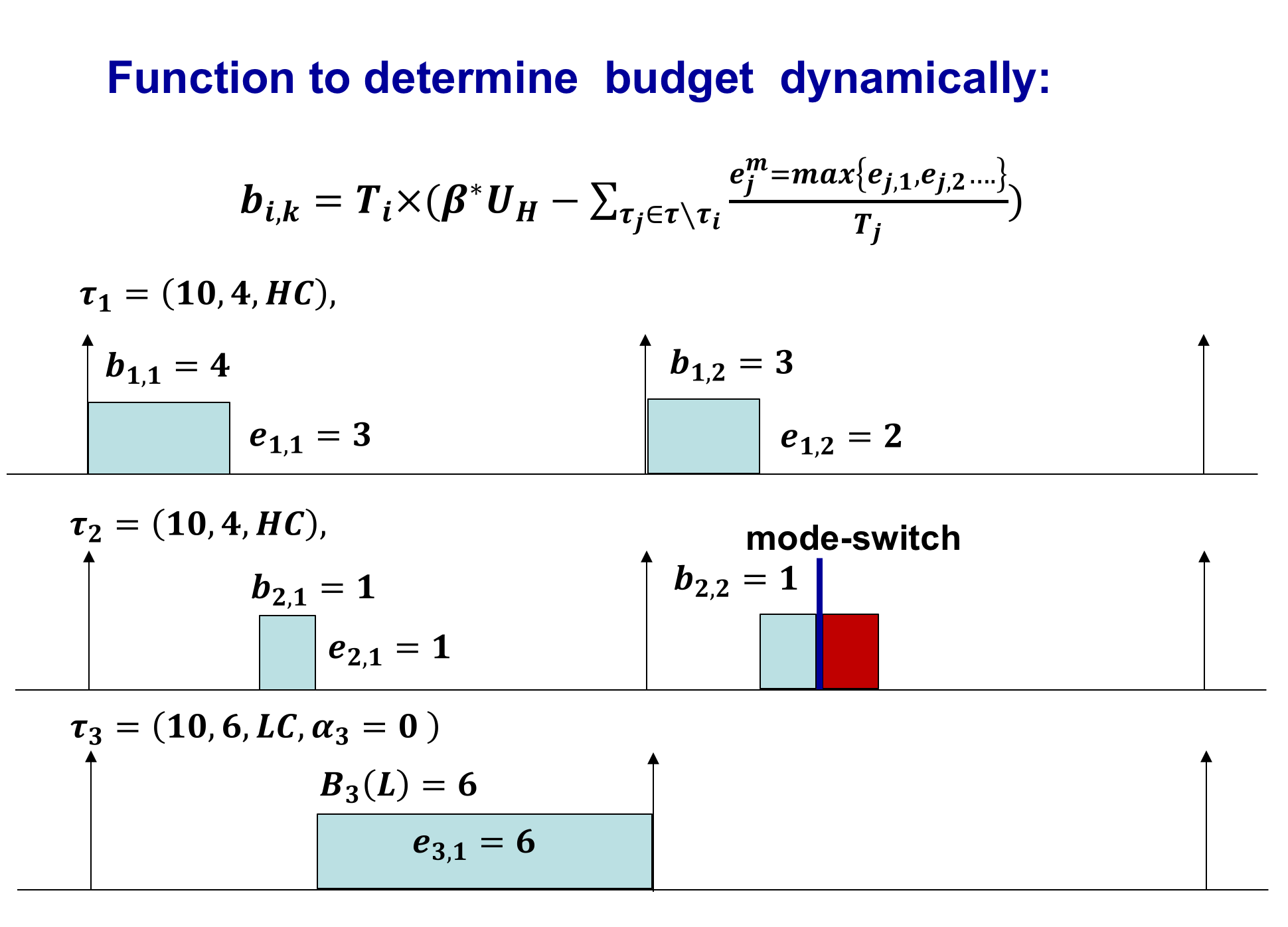

We have also developed a dynamic budget-based mixed-criticality task and scheduling model to address the above problem. In this model, high critical task budgets are determined at runtime depending on individual task execution requirements. Offline, we determine a total feasible budget allocation for all the high critical tasks combined under practical worst-case conditions. This budget is then efficiently managed online with the objective of providing as much computational resources as possible for the less critical tasks. To ensure safety even under theoretical worst-case conditions, the less critical tasks are degraded in the eventuality that the high critical task requirements exceed the allocated total budget.

2. Mixed-criticality scheduling for multicores

To meet the growing processing demands of mixed-criticality systems, multicore processors are increasingly being deployed due to their SWaP characteristics. In this work, we consider the problem of scheduling mixed-criticality systems on a homogeneous multicore processor platform.

To meet the growing processing demands of mixed-criticality systems, multicore processors are increasingly being deployed due to their SWaP characteristics. In this work, we consider the problem of scheduling mixed-criticality systems on a homogeneous multicore processor platform.

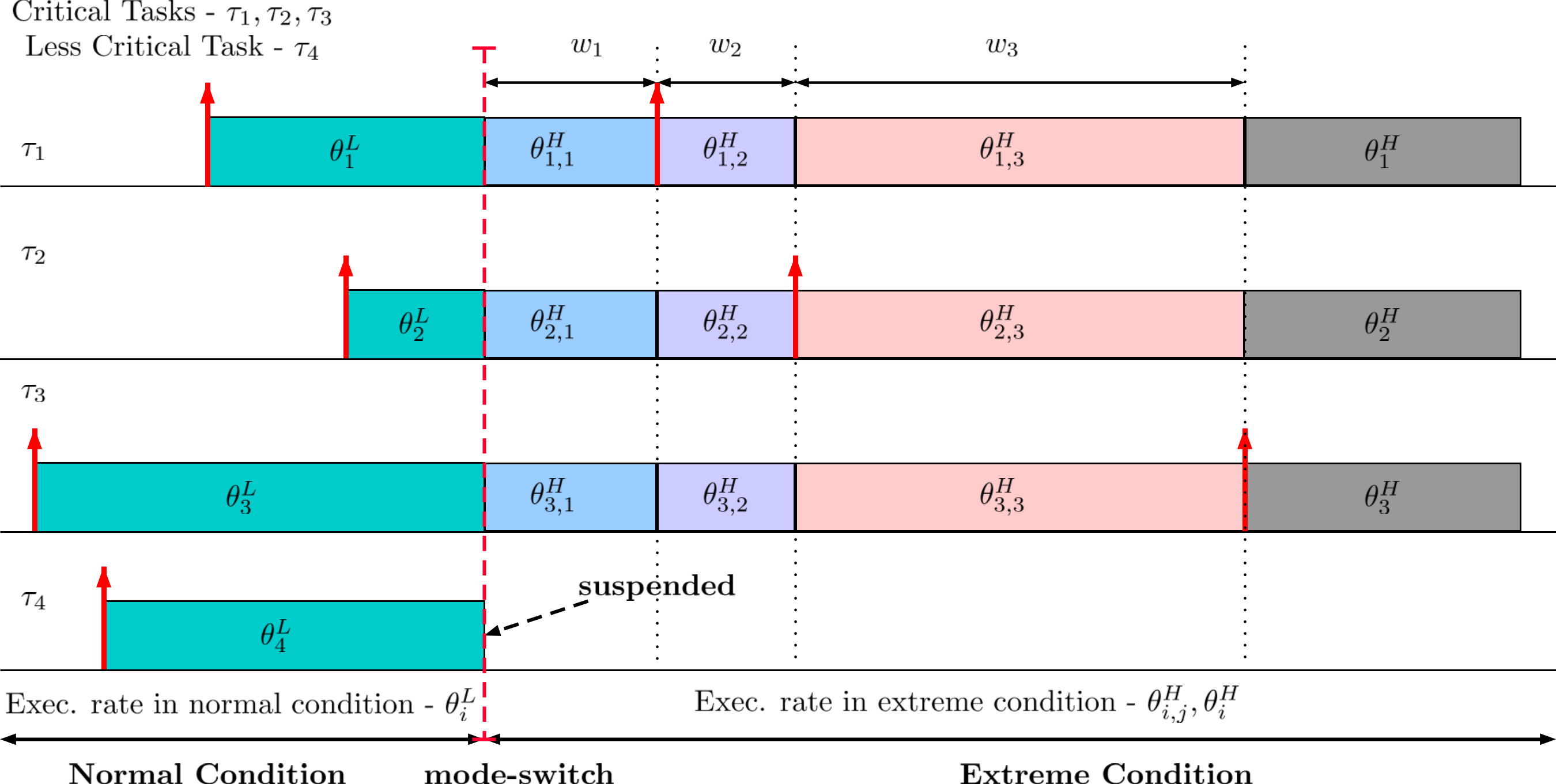

We have developed a fluid execution rate based scheduling model to address the above problem. In this model, the less critical tasks execute using a single fractional execution rate and the critical tasks execute using two fractional rates. Execution rate of the critical tasks vary depending on whether the system is experiencing normal or extreme worst-case conditions. During extreme worst-case conditions, the critical tasks execute at a higher rate than they would do normally, and the less critical tasks are suspended. These task execution rates are determined offline using an efficient convex optimization formulation, and the resulting scheduling policy is shown to have an optimal speed up bound of 4/3. To further improve performance, we have also extended this model to allow the critical tasks to use multiple execution rates during extreme worst-case conditions. As multiple critical tasks simultaneously require additional resources in such conditions, using fine-grained management of their execution rates we are able to achieve a higher resource utilization.

We have also developed an efficient partitioning (task-to-core mapping) strategy to address the multicore scheduling problem. Under this strategy, the critical tasks are allocated based on the principle of distributing the addtional demand, i.e., the difference in resource requirements between normal and extreme worst-case conditions, evenly among all the cores. Less critical tasks are allocated using a simple first-fit strategy. By balancing this additional demand, we are able to reduce the pessimism in mixed-criticality schedulability tests that are applied on each core, thus improving overall schedulability.

3. Mixed-criticality in automotive systems

The need for a good degradation model for MCS in safety-critical domains such as automotive is well recognized by the real-time systems community. When timing faults such as a deadline miss by a real-time task is imminent, a good degradation model can play an important role to prevent violation of system safety requirements. Guidelines for achieving graceful degradation of a safety-critical application is specified in functional safety standards such as ISO 26262 (for automotive), DO-178C (avionics), etc. The main challenge is to come up with a degradation model which is precise enough to consider these requirements leading to a computationally efficient verification methodology of its timing behaviour.

The need for a good degradation model for MCS in safety-critical domains such as automotive is well recognized by the real-time systems community. When timing faults such as a deadline miss by a real-time task is imminent, a good degradation model can play an important role to prevent violation of system safety requirements. Guidelines for achieving graceful degradation of a safety-critical application is specified in functional safety standards such as ISO 26262 (for automotive), DO-178C (avionics), etc. The main challenge is to come up with a degradation model which is precise enough to consider these requirements leading to a computationally efficient verification methodology of its timing behaviour.

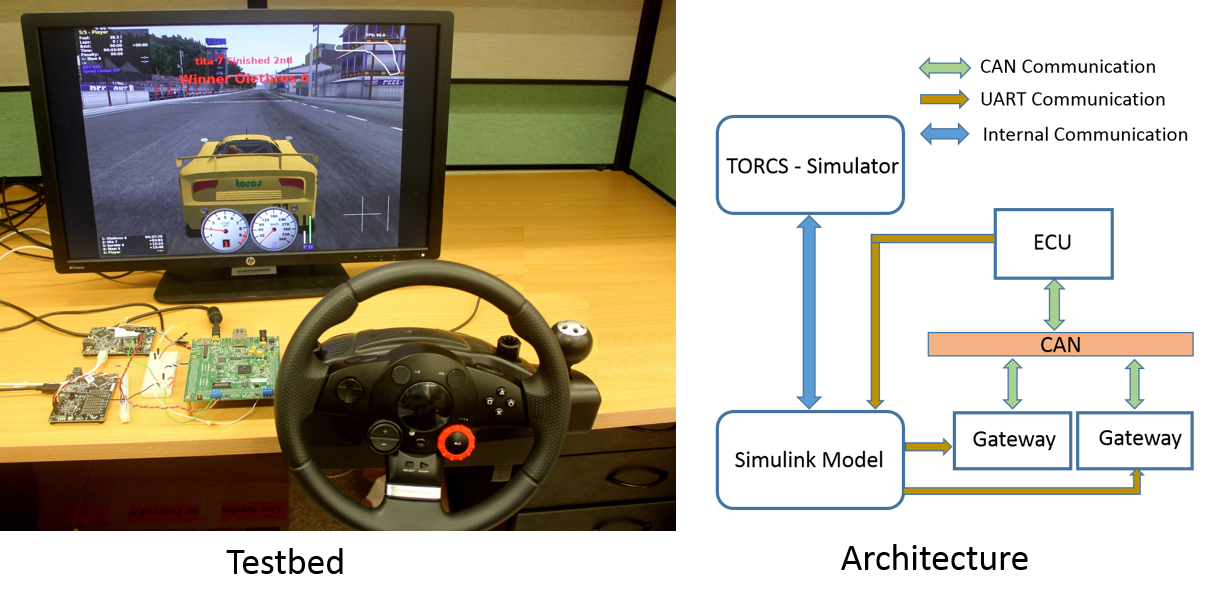

In order to study the effect of different degradation models in the performance of safety-critical applications, we have developed a simulation-based automotive testbed. Applications considered for this implementation are Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC), Collision Avoidance (CA) and Steering Control (SC). These applications are of different criticalities and share sensor values such as velocity, position and acceleration, of follower and lead vehicles, and actuators such as brake, steering and throttle. The testbed is a Hardware-In-The-Loop simulation platform. It comprises five major components: vehicle simulator, simulink model, gateway, Electronic Control Unit (ECU) and Controller Area Network (CAN). It uses The Open-source Race Car Simulator (TORCS) as a vehicle simulator, which provides physics-based vehicle models and different road terrains. The simulink model running in a Personal Computer (PC), acts as an interface between TORCS and the gateway. The gateway consists of embedded controllers (FreeScale Kinetis Board) networked over an industry standard CAN bus which converts the simulated sensor values from TORCS to CAN messages. Texas Instruments Hercules development board acts as an ECU. The ECU runs FreeRTOS, which uses a preemptive fixed-priority based real-time scheduler and hosts all the applications. This testbed provides the following features:

- Simulate different driving scenarios and task execution patterns where the occurence of timing faults becomes imminent.

- Observe the effect of task degradation models that affect the application’s performance and also possibly safety.