Research Motivation

The era of Industry 4.0 brings increased connectivity among devices, predictability through a large volume of data, and an ability to accurately capture states of the manufacturing shop-floor. Digital twin is a realistic virtual representation of machines or any form of living or non-living physical things that can accurately monitor, predict and optimize their operations. Although digital twin has received considerable attention recently in various domains such as manufacturing and cloud computing, etc., there is a number of limitations in the existing works:

- Lack of support for various modeling formalisms that integrate with online data for creating a scalable twin.

- Many focus on the traditional off-line simulation of high-fidelity models.

- Most architectures are missing the details on how digital twin models are composed with each other using a formal model of computation.

Contributions

To build an accurate view of the physical system via a digital twin, the software architecture should support the utilization of different modeling strategies for creating the twin, where each model specializes in certain application domains. Furthermore, it is essential to support a method to combine such heterogeneous models in a consistent manner and utilize gathered online data from a physical system to provide a holistic understanding of the physical system’s state.

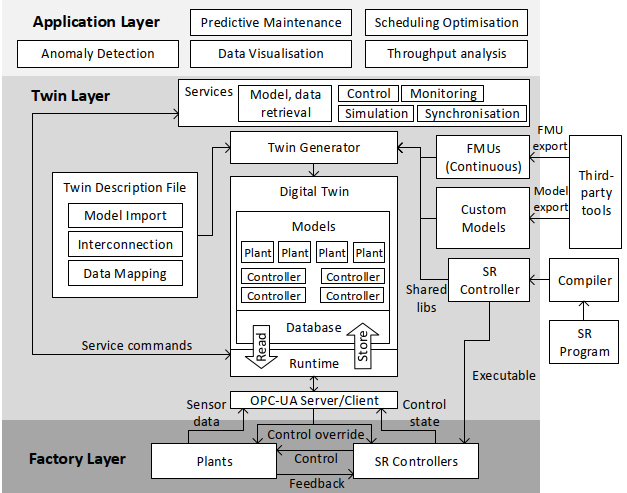

1. The Architecture

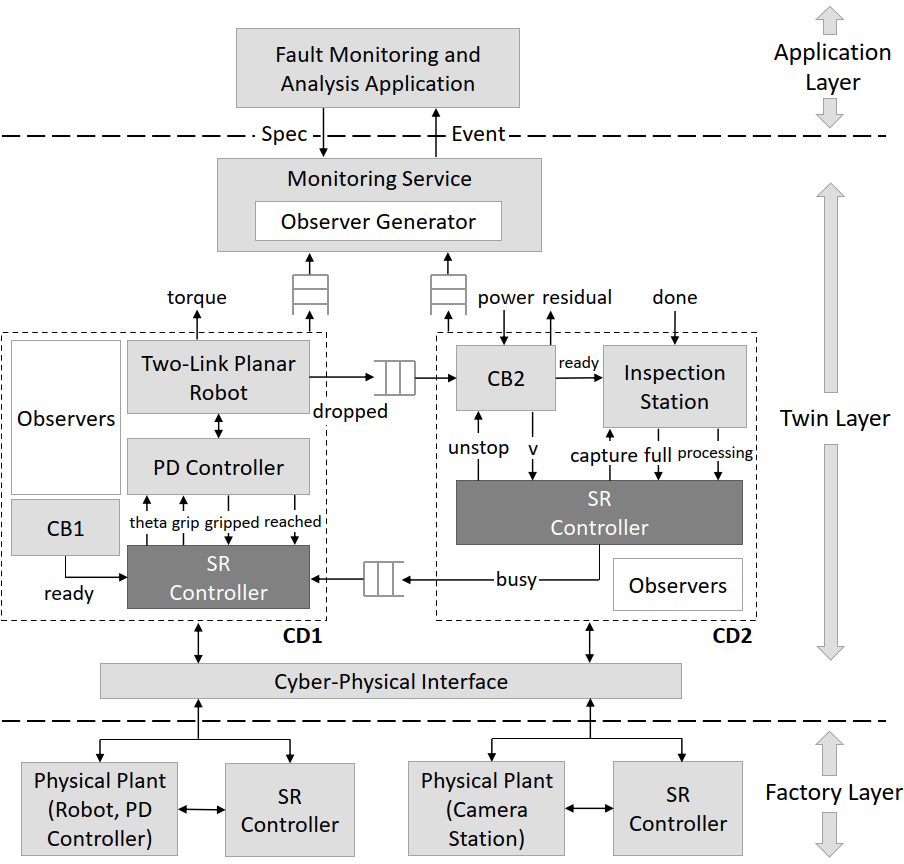

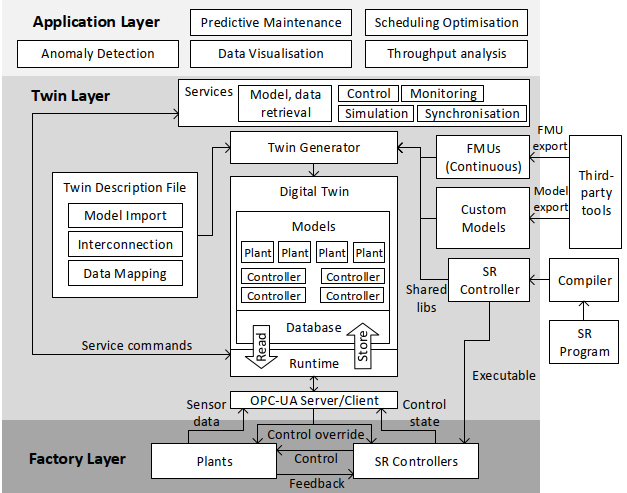

Our digital twin architecture consists of three layers. Each layer has a number of facilities that help the higher-level layers to perform more concrete tasks.

Our digital twin architecture consists of three layers. Each layer has a number of facilities that help the higher-level layers to perform more concrete tasks.

- Factory Layer has a set of physical assets and devices that control the manufacturing process and forwards data to the level above via the cyber-physical interface.

- Twin Layer is a fundamental part of the architecture that consists of twin models, online data, and various services for realizing the digital twin’s modes of operations: control, monitoring, and simulation. Examples of models that can be imported into our architecture are Functional Mock-up Units (FMUs), Petri-Net, Esterel, FSMs

- Application Layer interacts with the digital twin for different use-case scenarios such as throughput monitoring, predictive maintenance, scheduling optimization, etc.

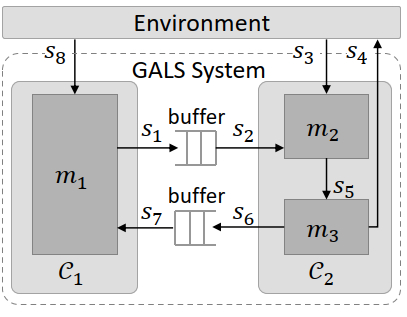

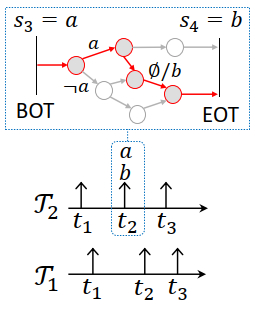

2. Globally Asynchronous Locally Synchronous Semantics for Digital Twin

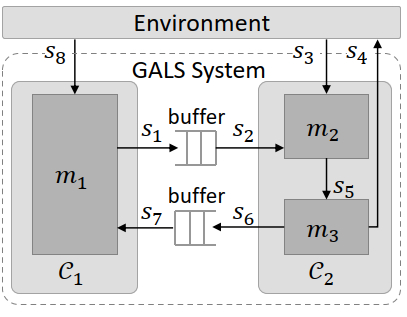

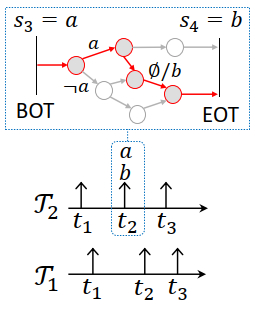

Intuitively, plants and controllers in our digital twin are heterogeneous models following Globally Asynchronous Locally Synchronous (GALS) model of computation (MoC) on a top level. The main features of our GALS MoC are:

Intuitively, plants and controllers in our digital twin are heterogeneous models following Globally Asynchronous Locally Synchronous (GALS) model of computation (MoC) on a top level. The main features of our GALS MoC are:

- Execution of a digital twin model is based on a sequence of logical ticks. In addition, a tick has its corresponding value in the continuous time domain.

- Local execution determinism based on the Synchronous Reactive (SR) semantics, which is a subset of GALS.

- Global asynchrony and communication between models in different clock-domains via First-In-First-Out (FIFO) buffers.

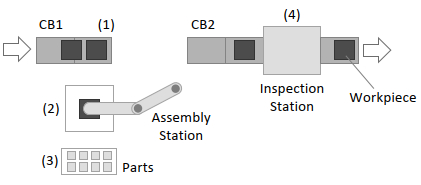

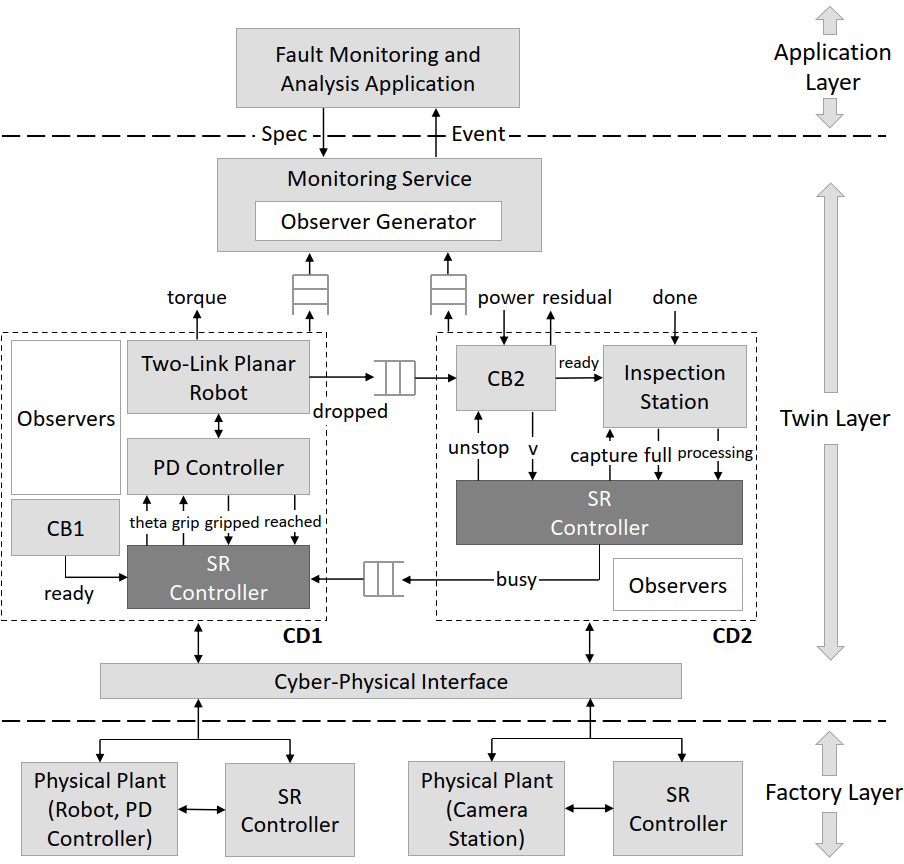

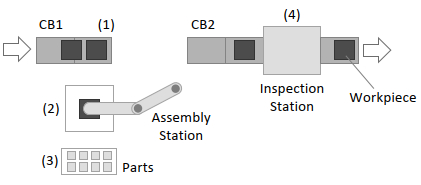

3. Case Study 1: Fault Monitoring and Analysis for the Manufacturing System

The role of the fault monitoring and analysis application is to find the root cause of abnormal activities in the physical system via the digital twin by utilizing both the online data and the models of the twin. Detection of two different types of faults is illustrated based on the workpiece inspection time

- A fault in the conveyor belt’s actuator. In this scenario, a fault is indicated by intermittent spikes in the instantaneous power spectrum of the induction motor due to the induced motor stator current from the unbalanced rotor

- A fault in the actuator of the two-link planar robot. A control algorithm for the workpiece placement on the conveyor belt is disturbed by actuator fault in the robot manipulator. This results in the misalignment of workpieces that causes increase in delays in the inspection process. The actuator fault in this scenario gradually drifts the manipulator’s joints from the actual torque reference set by the controller

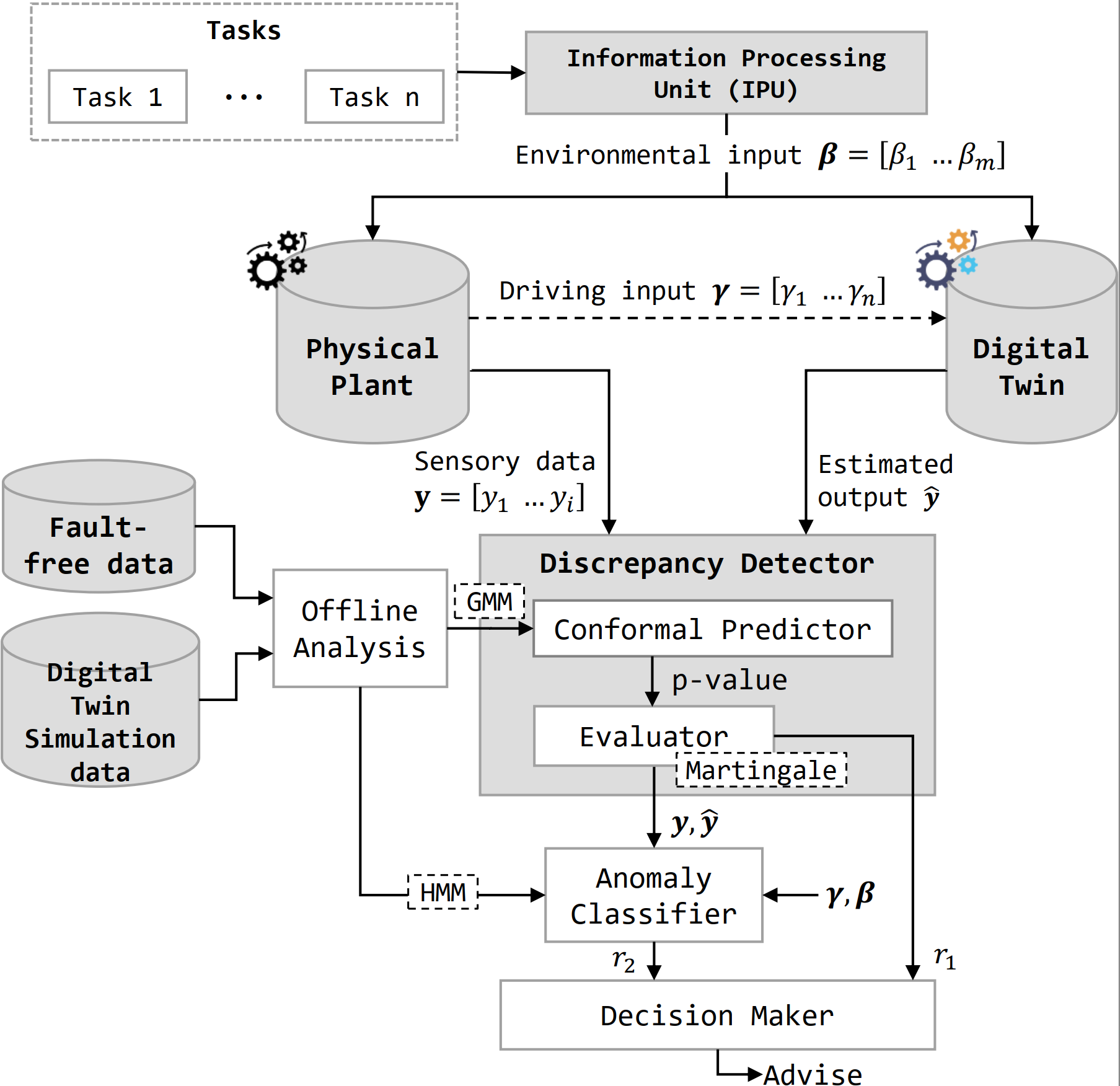

4. Anomaly Detection Framework for Digital Twin

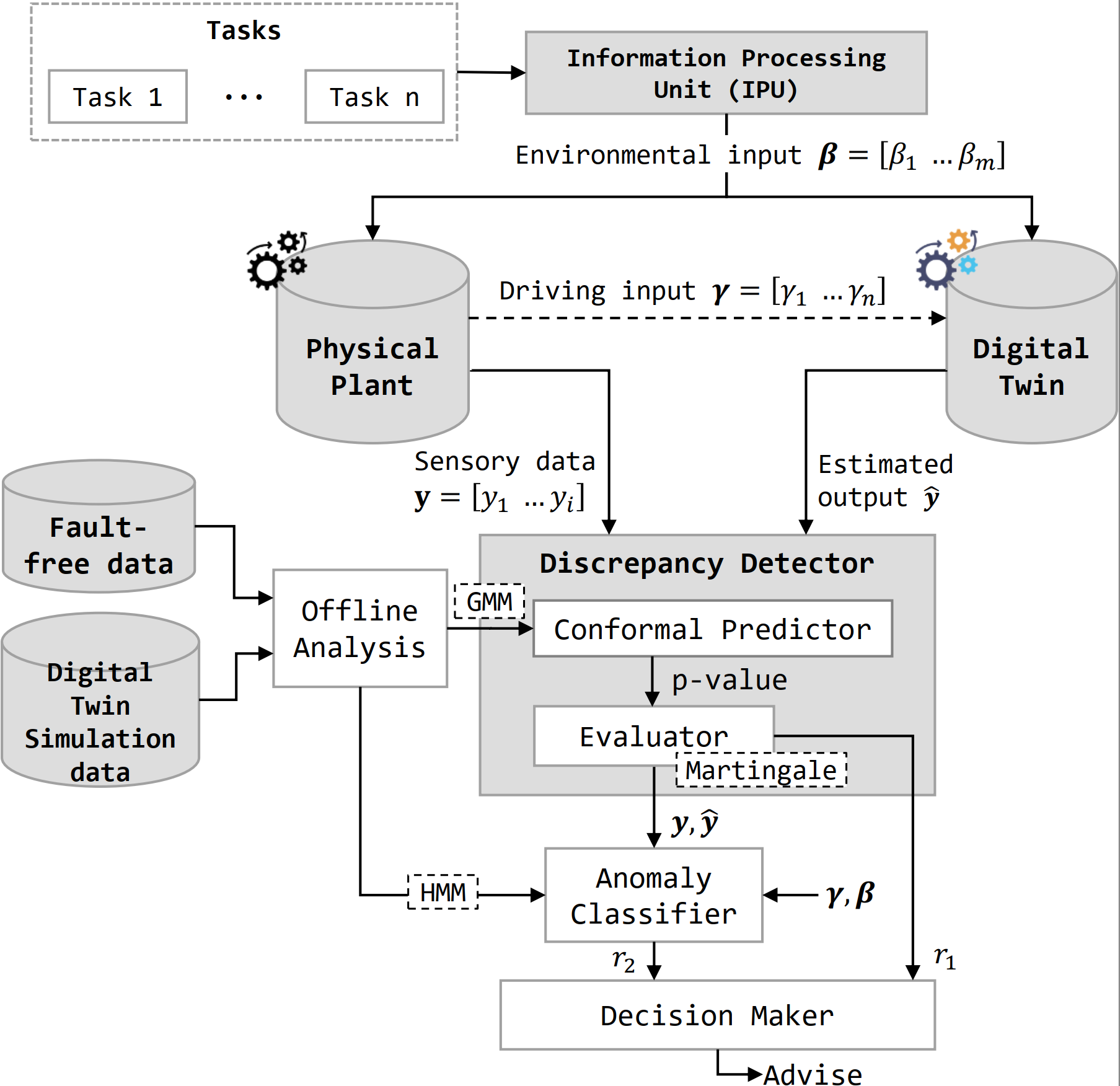

The anomaly detection framework aims to detect the online process anomalies and determine the anomaly sources for large-scale digital twin based Cyber-Physical System. This framework integrates both the digital twin and data-driven techniques and can differentiate the anomaly sources among digital twin, physical plant, and sensor measurement. To generalize the framework, the internal details of the digital twin are not required such that the digital twins whose internal information are not accessible can also be applied. The main features of the framework are:

- Discrepancy Detector is used to monitor the discrepancy between physical plant measured value and digital twin predicted result. In this framework, the discrepancy detector is designed based on Gaussian Mixture Model and Exchangeability Martingale.

- Anomaly Classifier is used to monitor the incoming data stream from physical plant measured data. The Hidden Markov Model is used in the anomaly classifier to monitor the relationship change of a group of variables which are divided by KMedoids algorithm.

- Decision Maker utilizes the results of the discrepancy detector and anomaly classifier to determine the anomaly source among digital twin, physical plant, and sensor measurement.

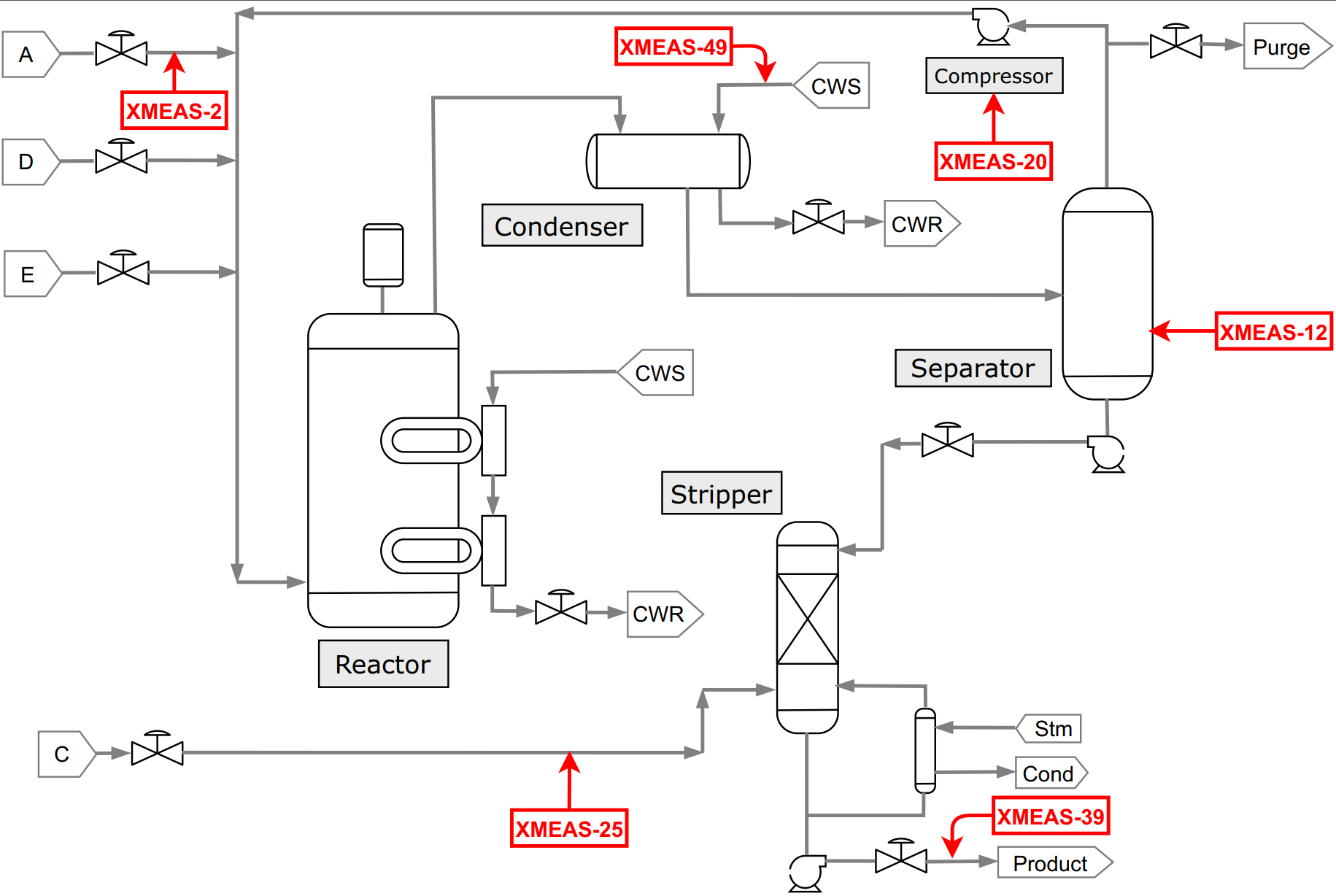

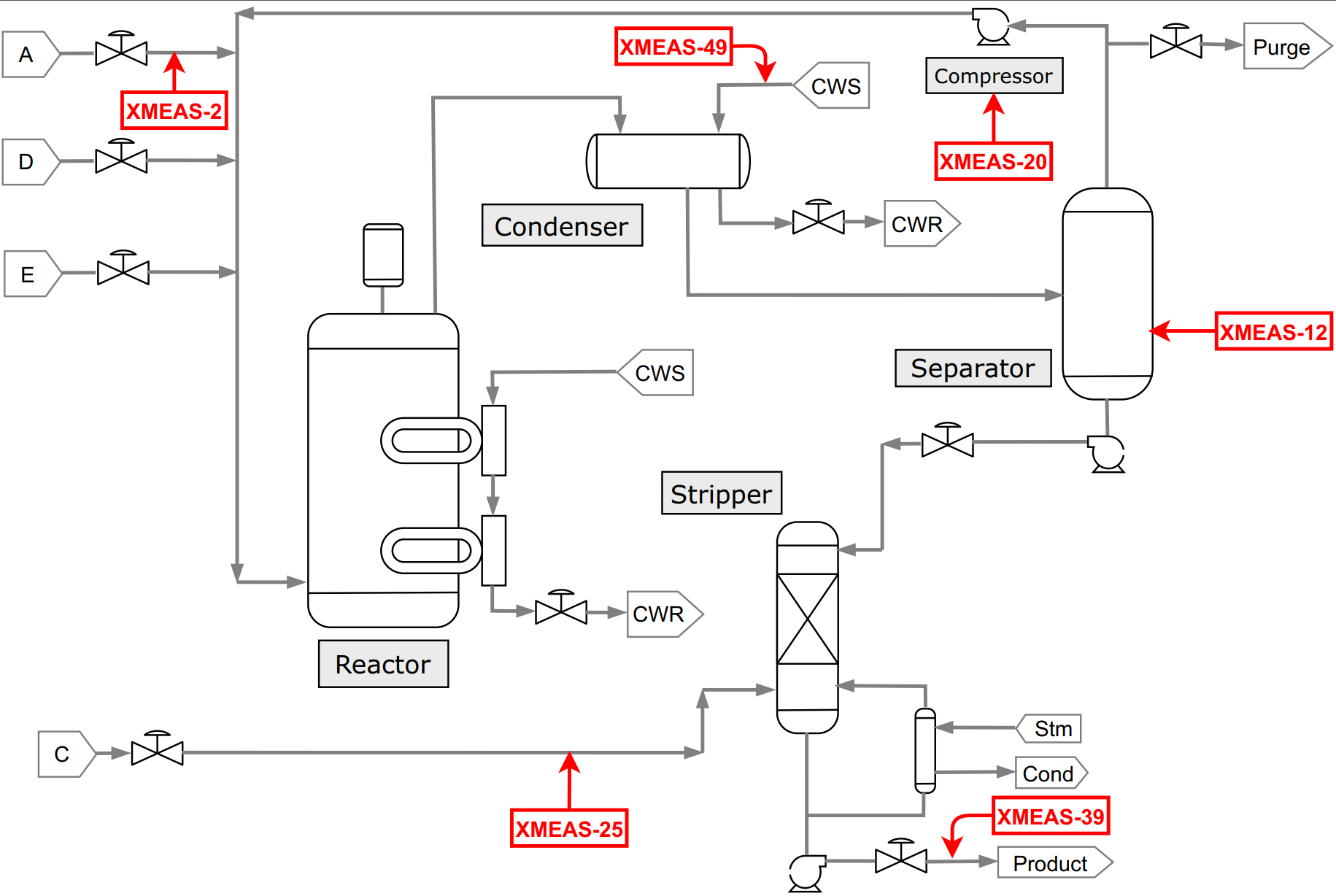

5. Case Study 2: Anomaly Detection for Tennessee Eastman Process

The Tennessee Eastman Process model is originated from an actual industrial process of Eastman Chemical Company. Four different types of anomaly have been designed with this model to test the performance of the anomaly detection framework:

- Anomalies from the Sensor Measurements. Sensor measurement fault can be classified into the following categories: drift faults, offset faults, erratic faults, spike faults, and stuck faults. Each type of sensor measurement faults is tested on several different sensors to verify the anomaly detection framework performance.

- Anomalies from the Faults in the Physical Plant. The tested physical plant anomalies include: feed loss of chemical A, reaction kinetics slow drift, chemicals A and C feed pressure random variation, and reactor cooling water valve sticking together with D feed temperature step change.

- Anomalies due to the Lack of Modes in the Digital Twin Model. In modelling terminology, this is akin to mode switching in the hybrid system. During the digital twin construction period, some modes might not be built or fully verified, thus the correctness of the digital twin in certain modes are not guaranteed. This scenario is designed to determine the performance of the anomaly detection framework on missing mode or digital twin faults.

- Anomalies dur to Multiple Sources. Here we define the anomaly sources are digital twin, physical plant, and sensor measurement. In practical, the anomalies can be caused by multiple sources. In the experiment, the sensor measurement faults and missing modes are both designed to happen at the same time to verify the framework performance.

Our digital twin architecture consists of three layers. Each layer has a number of facilities that help the higher-level layers to perform more concrete tasks.

Our digital twin architecture consists of three layers. Each layer has a number of facilities that help the higher-level layers to perform more concrete tasks.

Intuitively, plants and controllers in our digital twin are heterogeneous models following Globally Asynchronous Locally Synchronous (GALS) model of computation (MoC) on a top level. The main features of our GALS MoC are:

Intuitively, plants and controllers in our digital twin are heterogeneous models following Globally Asynchronous Locally Synchronous (GALS) model of computation (MoC) on a top level. The main features of our GALS MoC are: